This post was originally published in the 1800’s Housewife daily newsletter, on January 16, 2023. Not on the mailing list? You can join here to receive the daily recipe and cooking notes straight to your email.

Hi there, friends –

Today’s recipe is late coming to you, because I neglected to bookmark the particular recipe I intended to make and share, and could not find it again. “How many cookbooks from 1883 does the woman have?” You might ask. ONE. I have one.

Funny thing about 1800’s cookbooks. Even when they do have an index, these frequently are not exhaustive, containing just the “highlights” or recipes that presumably the editors thought might be most searched-for. And sometimes recipes get printed in sections one might not expect…for example, blackberry jam in the ‘remedies for invalids’ chapter.

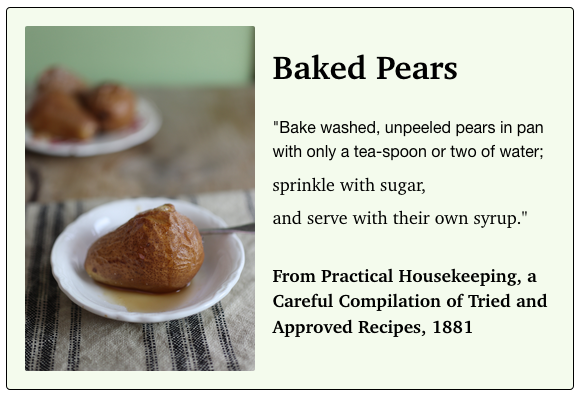

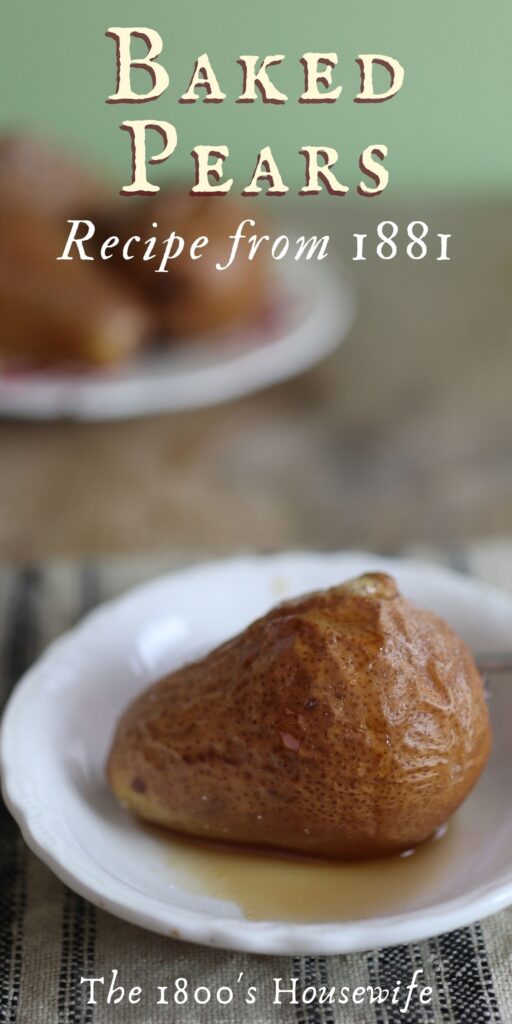

This baked pears recipe is from 1881, and extremely similar to the one I’d planned to make. And along with it, I’m including something extra–a photo of the clipping that was used to bookmark the page with this recipe. Bookmarking recipes you don’t want to lose track of…what a great idea!

~ Anna

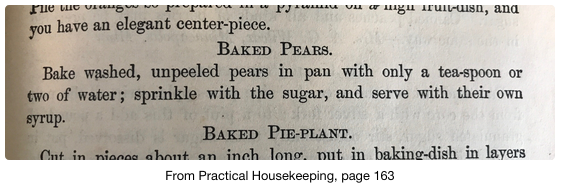

Here’s a photo of the recipe as it appears in the cookbook:

A few things I noticed when making this recipe…

Soft, ripe pears do well when baked with just a very small amount of water as called for in the recipe. If your pears are on the hard side, measuring that “tea-spoon or two of water” on the generous side, ends up being beneficial.

BAKING TEMPERATURE

Some 1800’s baked fruit recipes specify cooking them in a “slow” oven. So that was my approach when making this one. I used an oven temperature of 325°F. This worked really well, and resulted in perfectly-textured, sweet and soft pears, with an almost caramelized “syrup” in the bottom of the pan. This took about an hour and ten minutes for medium sized bartlett pears.

HOW TO KNOW WHEN THE PEARS ARE DONE?

Baked pears should be very soft, all the way through. Some other nineteenth century pear recipes specify that pear flesh should be translucent when they’re well cooked. I’ve found that pears seem to reach that perfectly-done stage when they still hold their shape (you don’t want them collapsing into mush), but a toothpick or skewer meets almost no resistance when inserted into one of the pears.

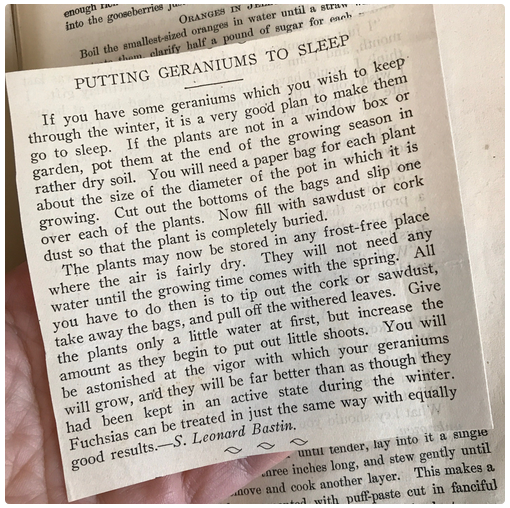

As promised, here’s a photo of the more-recent (but still old!) clipping that was used as a bookmarker in the page containing this recipe. You never know what you’re going to find tucked between the pages of an old cookbook!

Keep your eyes open tomorrow for our first ‘Tuesday tips’ email. I’ll be sharing some advice from 1832 on the health benefits of blackberries, as well as that “medicinal” blackberry jam recipe from 1845. Until tomorrow, ~ A

Denis Ostroot says

Absolutely perfect. Exactly what I was after! Thank you.