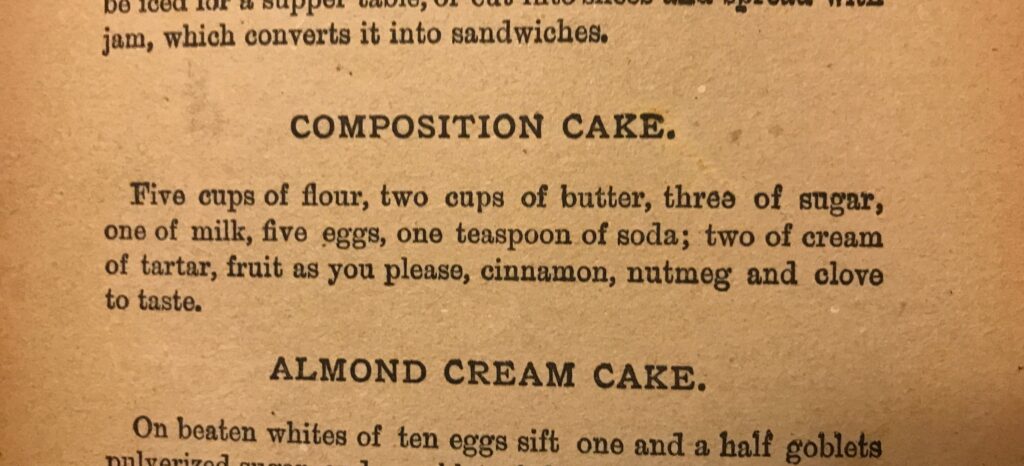

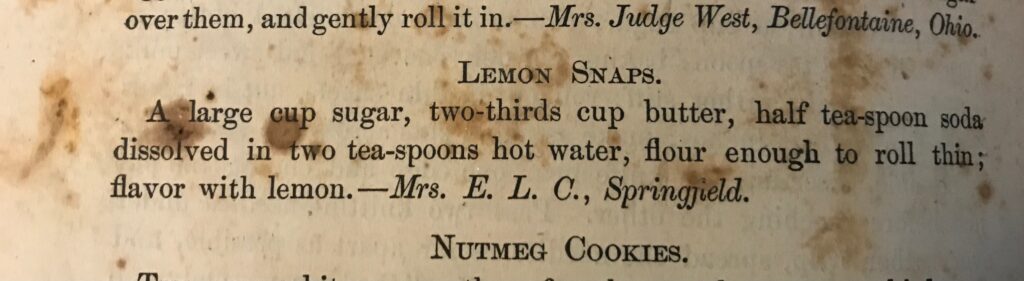

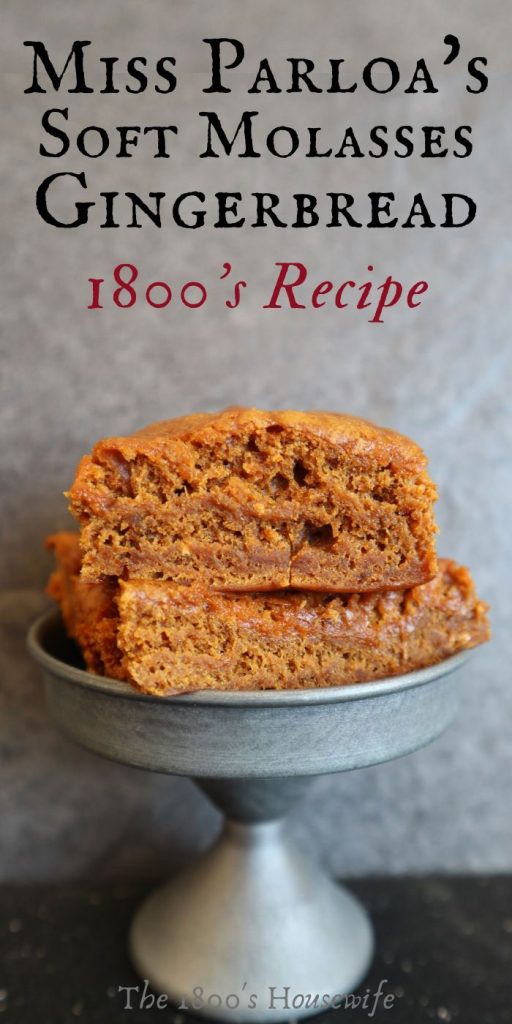

We’ve made some delicious recipes over the last few weeks. Composition Cake, really good Gingerbread, those ridiculously delicious little Lemon Snaps.

If you’d told me that Deviled Eggs of all things would end up on my list of favorite recipes from this project, I would have been dubious at best. But dear reader, these are just that delightful.

They’re a far cry from the sloshy Miracle Whip concoctions that graced many a church potluck table of my childhood. The tang of the vinegar, that hint of spice from the cayenne, the familiar warmth of the mustard…it all just works.

Next time I go to a church potluck, I’m bringing these.

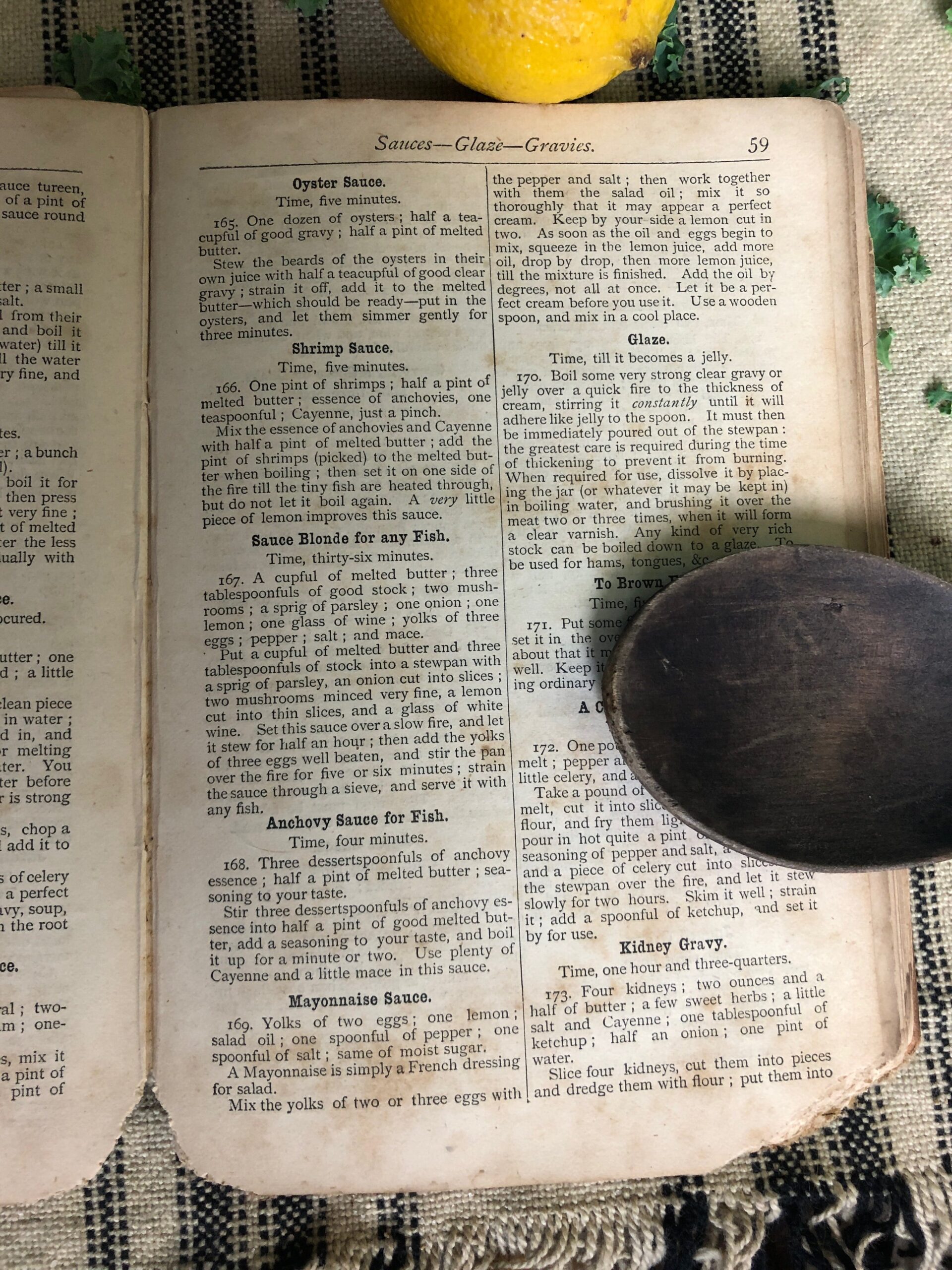

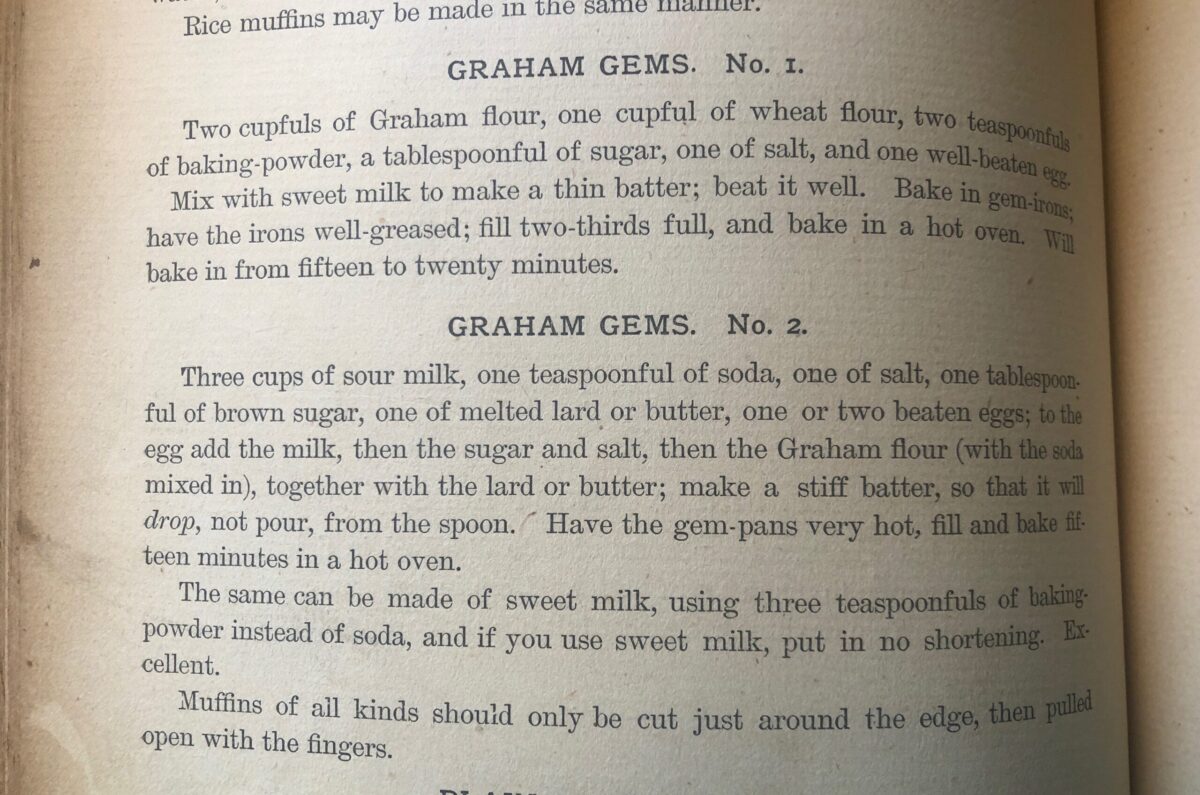

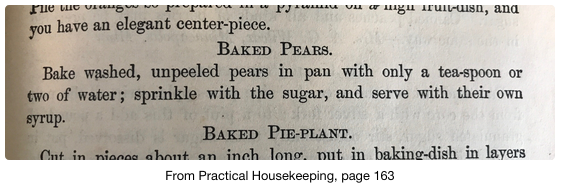

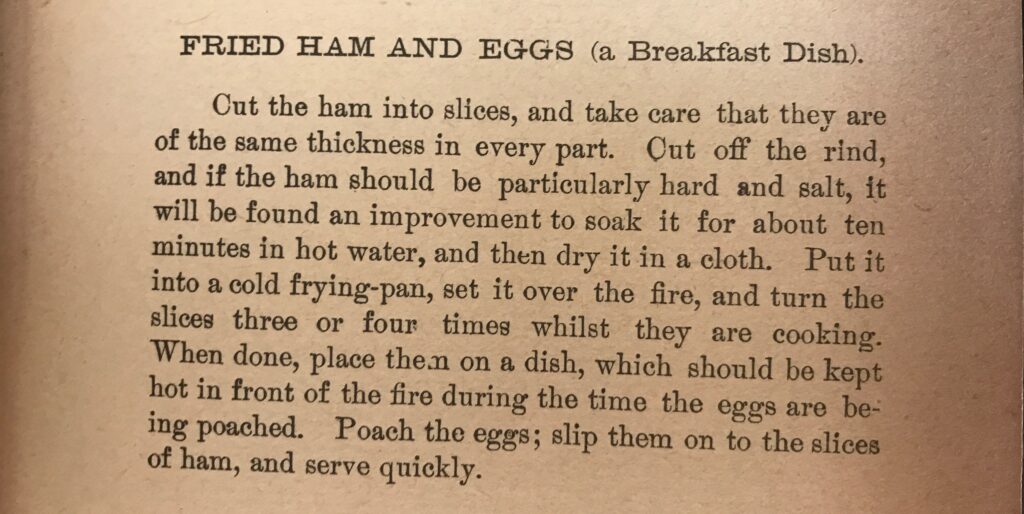

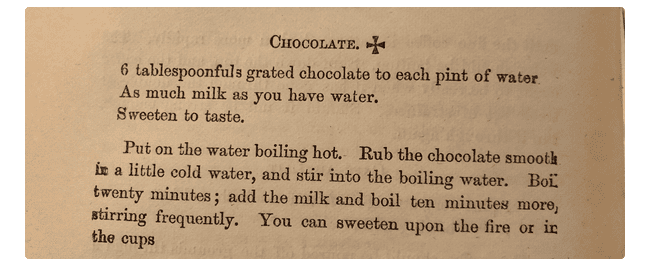

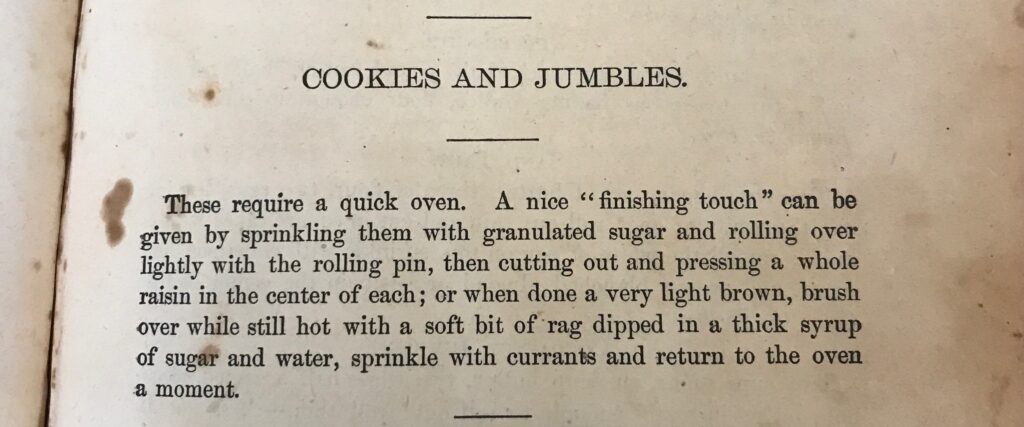

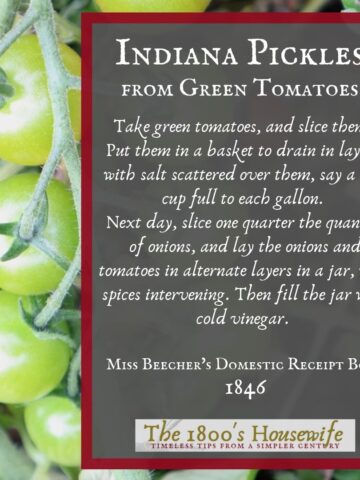

Here’s a photo of the recipe as it appears in the cookbook:

A FEW COOKING NOTES:

This quick little recipe hardly needs notes, but here are a few comments on how I made it.

INGREDIENT AMOUNTS:

For six eggs, I found that 4 teaspoon of butter seemed needed to keep this from being too dry. For spices, I used ⅜ teaspoon cayenne, ¼ teaspoon mustard, and 1 teaspoon of apple cider vinegar. I loved it, and would enjoy these a little spicier if I weren’t sharing them with my kids.

THAT SALAD:

Not finding cresses to be had, “not even for ready money”, I went with a spring mix that had some nice texture to it. When adding the vinegar, salt, pepper, and sugar, I found that this whole thing works best if you toss the salad along with the accoutrements, to get it evenly and lightly coated. Then pile it on your serving tray.

à la COLUMBUS:

If that reference escapes you (and it did me at first), here’s what this is referring to. This pairs well with a quick read about Tesla’s Egg of Columbus exhibit at the world fair, because that’s fascinating too. (Although that exhibit wouldn’t come along until another 16 years after this cookbook was published.)

IS IT ‘DEVILED’ OR ‘DEVILLED’?

I’m going to quote the website, Grammarist on this one:

Deviled is the accepted spelling in the United States and Canada for an adjective describing food that is seasoned with horseradish, mustard, paprika or pepper to impart a strong flavor. In other English-speaking countries, the spelling is devilled.

This cookbook does seem to have a slightly more British vocabulary than some other American cook books of the same era. But also, perhaps the two spellings hadn’t yet diverged in the 1870’s. Interesting, isn’t it?

📖 Recipe

Devilled Eggs

From Common Sense in the Household, 1877

The tang of the vinegar, that hint of spice from the cayenne, the familiar warmth of the mustard...this bright and flavorful party dish is just delightful.

Ingredients

- 6 eggs

- 4 teaspoon butter

- ⅜ teaspoon cayenne

- ¼ teaspoon mustard

- 1 teaspoon of apple cider vinegar

- 5 ounces cresses or mixed greens

- for the greens: salt, pepper, vinegar and sugar to taste

Instructions

- "Boil six or eight eggs hard;

- leave in cold water until they are cold;

- cut in halves, slicing a bit off the bottoms to make them stand upright, à la Columbus.

- Extract the yolks, and rub to a smooth paste with a very little melted butter, some cayenne pepper, a touch of mustard, and just a dash of vinegar.

- Fill the hollowed whites with this, and send to table upon a bed of chopped cresses, seasoned with pepper, salt, vinegar, and a little sugar. The salad should be two inches thick, and an egg be served with a heaping tablespoonful of it. You may use lettuce or white cabbage instead of cresses."