This post was originally published in the 1800’s Housewife daily newsletter, on January 14, 2023. Not on the mailing list? You can join here to receive the daily recipe and cooking notes straight to your email.

Yesterday we got about 7 inches of heavy, early-morning snow, followed immediately by rain. The result, of course, was slushy, ankle-deep snow soup. I found that everything from feeding the ducks, to getting the car out of the driveway, ended up feeling an awful lot like one long, cold and wet, patience-building exercise.

How comforting to settle in at the end of that day, with a strong cup of this 1800’s “drinking chocolate”. Whether you’re a fellow New Englander slogging through snow soup, or one of our southern readers–you deserve this recipe as much I do, and I hope you enjoy it every bit as much!

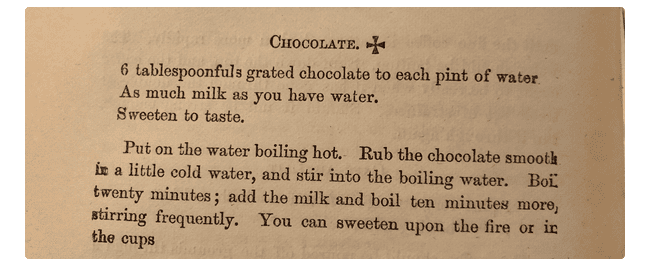

Here’s a photo of the recipe as it appears in the cookbook, page 494:

If you’d like to make this recipe taste as close to a nineteenth century cup of chocolate as possible, it can be helpful to know a bit about the chocolate that was readily available in the 1800’s.

When this cookbook was written, the bar of chocolate used for a recipe like this would have been an unsweetened bar of “family chocolate”, often bought in a one-pound bar. At least one manufacturer, McCobb’s, sold their “plain chocolate” bar in a tin with a built-in grater. You can see one of these right now on eBay, which is kind of neat.

This wasn’t milk chocolate, which wasn’t widely available until about the turn of the century. And it wasn’t smooth, like we’re used to today, since the conching process that produces silky-smooth chocolate wasn’t invented until 1879. This would have been a bit of a grittier, dense-feeling chocolate.

So what kind of chocolate should you use to recreate this recipe? When I’m being intentional about choosing chocolate to most authentically recreate this, or other 1800’s drinking chocolate recipes, I buy the least-sweetened stone ground chocolate that I can get my hands on. Taza’s 95% Wicked Dark is a good bar for this.

Many folks opt to use unsweetened baker’s chocolate for re-creating vintage recipes, which has the benefit of being inexpensive and readily available. This also works great, and makes for a delicious cup of chocolate.

Because texture does play such a role, I personally feel that given the choice between an unsweetened but modern-smooth bar, or a barely-sweetened stone ground bar, the stone ground option is a closer approximation of what the average person would have been using for making hot chocolate in the mid-to-late 1800’s. (If you’d like a deeper dive into chocolate history from 1850-1900, this is one of the more thorough sites, and a very interesting read.)

How much sugar should you add? Like most chocolate recipes of the time, this is left totally up to personal preference. As Marion Harland says in the recipe, “sweeten to taste”. I find that about half a teaspoon in a 6 ounce cup of this hot chocolate is what I enjoy.

It’s worth keeping in mind that we go through a vastly greater amount of sugar per-person, in modern America, compared to what was used in the 1800’s. Chocolate was generally sweetened much less than what we’re now used to, and I’ve really come to enjoy it that way.

Keep your eyes open tomorrow for an 1800’s recipe for ham with eggs. Until then, Anna

Comments

No Comments